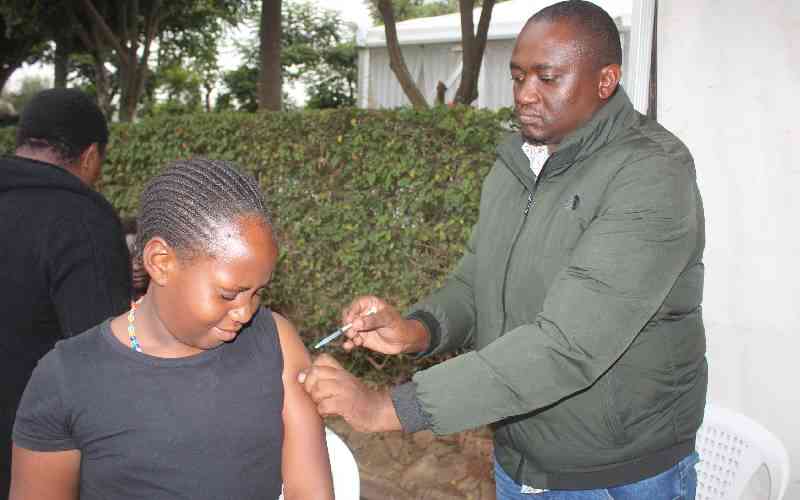

A medic from Mater Hospital administers the typhoid vaccine to a child during the wellness clinic in Buruburu, Nairobi, on July 13, 2025. The campaign for mass vaccination for typhoid and measles ends on July 14, 2025. [Benard Orwongo, Standard]

Typhoid fever remains a serious public health challenge for both the public and the medical community.

This is mainly due to the failure by stakeholders to enforce key preventive measures — such as proper sewage disposal, effective water drainage, safe garbage management, building pit latrines in rural areas, handwashing with warm water and soap after using the toilet and boiling drinking water thoroughly.

With rising medication costs and the Social Health Authority (SHA) under strain, reducing typhoid infections remains more theory than reality. Reports show an outbreak in 25 counties, and experts warn that poor hygiene and limited access to clean, safe water will keep the disease spreading in many parts of the country.

The rising number of illegal eateries in major towns across Kenya, often staffed by unvaccinated workers, is worsening the typhoid fever crisis. Worryingly, many food handlers in even well-known hotels lack valid health certificates proving they are vaccinated against air and waterborne diseases.

These food servers, especially in crowded areas, become unwitting carriers, spreading the disease to unsuspecting customers.

“Public health inspectors should shut down illegal food kiosks and ban the sale of food in open spaces. Owners of established food outlets must also ensure their staff are vaccinated against typhoid and hold up-to-date medical certificates clearly showing immunisation status and expiry dates.

- Health crisis brews as SHA halts monthly payments for millions

- SHIF deductions are legal, Duale says

- SHA's Sh100b digital highway fails to curb fraudulent claims

- Kenya to vaccinate children against typhoid and measles-rubella

Keep Reading

“Just like some travellers have been issued with fake yellow fever vaccination cards without actually being vaccinated, the same corruption and inefficiency has led to typhoid and cholera certificates being given to food handlers without proper medical checks or immunisation,” says Narshibhai Ghedia, Managing Director of Kenya Laboratory Supply Centre.

Ghedia warns that some laboratories also hire unqualified staff who fail to grasp the risks posed by unvaccinated food servers.

He notes that at many medical seminars on air and waterborne diseases, doctors have raised concerns about the alarming spread of typhoid fever. He urges the government to act boldly to implement the recommendations given at these forums to curb the disease’s spread.

In most cases, recommendations and proposals to curb typhoid fever remain on paper. One key step is to intensify immunisation campaigns targeting high-risk groups, especially travellers to endemic areas. People should also be advised to drink only boiled or treated water, wash raw vegetables thoroughly and sanitise unpeeled fruits with chlorinated water. These simple home based measures can prevent infection but are often ignored.

The lasting solution remains vaccination. Typhoid is not just a Kenyan problem, it affects millions worldwide. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates over 600,000 deaths every year, mostly in developing countries. In Kenya, the infection rate is about 11 percent, and many untreated cases end in death. Experts warn the actual figure could be higher due to gaps in data. The disease, spread through contaminated food and water, hits the poor hardest, especially in overcrowded, unhygienic areas. Considering the costs of treating typhoid fever, vaccination should be the first line of defence. “While vaccination provides an immediate benefit, it should be done alongside other home-based preventive measures,” says Dr Mohan Lumba, a medical consultant.

While the government has been urging parents through public health officers, media announcements and county administrators, to take their children for immunisation against measles and typhoid fever under expanded immunisation programme, turn up has not been impressive.

According to Ken Otieno from Kopiata Dispensary in Rarieda, Siaya County, only a few people turned up for immunisation at Migowa, Mituri, Lweya, Rageng’ni and Chianda centres on the first day of the exercise. “Just like with the Covid-19 vaccine, people are skeptical. We’re seeing a similar pattern with this typhoid campaign,” Otieno said during an interview at Mituri Primary School.

Just like cholera, food handlers remain a major source of typhoid infection. Mandatory vaccination would help reduce the spread, since even people of higher status eat in places where unvaccinated staff handle food.

Dr Lumba points out that classic symptoms like diarrhoea, vomiting, high fever and slow pulse rate are now rare. “This is due to antigenic shift or mutation of the bacteria,” he explains.

According to medical experts, the clinical presentation now commonly seen in Kenya is of mild illness, with minor abdominal disturbances, fatigue, slight headache, body ache and fever. Due to similarities with mild attacks of malaria, many patients infected with typhoid spend some time treating themselves for malaria. However, the symptoms are more dramatic in children given their weak immune system. The disease kills due to high fever and rupturing of ulcers in the intestines and must therefore be prevented before it strikes.

Typhoid awareness and prevention campaigns in Nyanza, sponsored by a multinational pharmaceutical company, were meant to run for three years but ended after just nine months when ministry officials began fighting over sponsorship money. The campaign focused on teaching the public about both home-based and medical ways to prevent the disease, with schools targeted because children often eat unsafe things such as chalk and soil.

A survey by the Kenya Medical Association (KMA) later showed that the short campaign reduced infection rates by 40 per cent. “Vaccines are for healthy people. Anyone can walk into a designated immunisation centre and get the jab. Once infected, treatment can be costly and involves strong antibiotics. That’s why prevention is always better than cure,” says Dr Lumba.

He adds that treatment usually lasts 10 to 14 days and should be done with the right antibiotics to prevent drug resistance. When caught early, typhoid can be treated successfully. Anti-typhoid vaccines are between 75 and 90 per cent effective.

The current typhoid vaccine administered by the government provides immunity for up to five years, says Dr Patrick Amoth, Director General at the Ministry of Health. “Maintaining good hygiene standards is important to ensure the success of the vaccines,” Dr Amoth told the press in Nairobi.

He urged parents to take children, from just a few months old up to 14 years, for both measles and typhoid immunisation. Slum areas, which face water shortages, poor sanitation and poor nutrition, have a high prevalence of typhoid, making vaccination the best option since it is offered free of charge.

“Conjugate vaccines have demonstrated a good immune response, they’re safe and well tolerated,” said Dr Amoth. He added that the typhoid vaccine will help reduce infections and deaths linked to the ongoing typhoid outbreak.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.