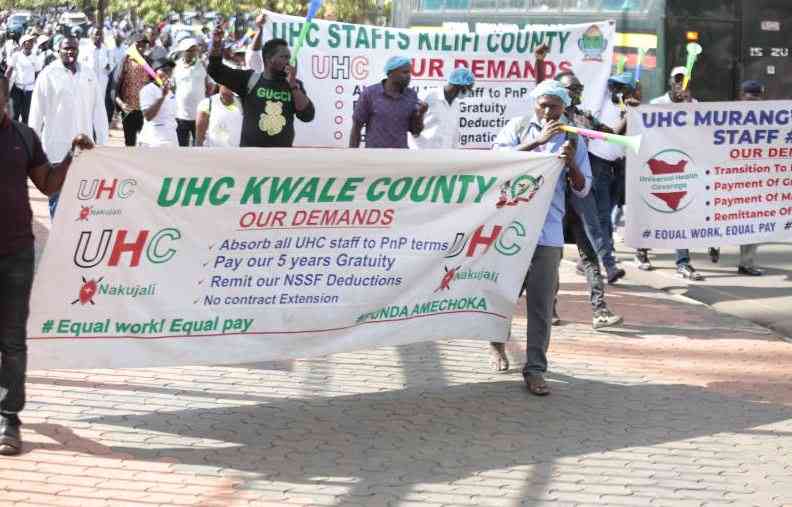

The much-publicised Universal Health Coverage (UHC) may remain a pipe dream unless urgent reforms are implemented, health experts have warned.

The Social Health Authority (SHA), tasked with financing UHC, has only collected Sh45 billion between October 2024 and July 2025, averaging Sh4.5 billion per month, far below the Sh54 billion annual target for 2024/25.

Despite registering over 23 million Kenyans, only 4.4 million are active contributors, giving SHA a contribution density of just 19 per cent. This is significantly lower than that of the defunct National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), which collected Sh74 billion in 2021/22, Sh76 billion in 2022/23, and Sh66 billion in 2023/24.

Risk pool

“This reform has worsened the situation, not improved it,” says health economist John Juma.

He warns the current model prioritised mass registration over sustained contribution, leading to a risk-heavy pool dominated by sick contributors.

Juma explains that salaried employees make up 77 per cent of contributors, while informal sector members comprise just 23 per cent. The average contribution from non-salaried members is Sh591, slightly more than NHIF’s flat rate of Sh500, but still too low to sustain operations.

Economist Prof XN Iraki notes that many Kenyans only pay premiums when ill. “There’s no culture of preventative health spending. People stop paying once they feel better.”

- Ministry, governors clash over ghost workers in health payroll

- Duale: Biometrics to replace OTP use in sweeping SHA reforms

- Government drops 215 UHC 'ghost workers' from payroll

- Ladnan Hospital denies links to SHA boss amid fraud claim

Keep Reading

SHA’s 2.75 per cent gross salary levy, meant as a solidarity contribution, has effectively become a burden on formal workers, subsidising the inactive informal sector.

Private and faith-based hospitals are now owed Sh33 billion, with another Sh32 billion in unsettled claims. Rural Private Hospitals Association (RUPHA) has threatened to suspend SHA services over non-payment, particularly for dialysis and cancer care.

Outpatient services, a central feature of Kenya Kwanza’s preventive health agenda, remain largely unavailable. A recent survey in Nairobi found patients turned away from SHA-covered outpatient units, pushing them to pay out-of-pocket—even at government-funded Level 2, 3, and 4 facilities.

SHA’s Sh104 billion digital infrastructure investment has failed to drive consistent premium collection. Experts argue the scheme lacks a compelling value proposition for families.

Juma recommends SHA focus on outpatient care, diagnostics, and essential medicines, frequent and relatable health expenses that build trust and drive participation.

He cites Thailand’s UHC model, which started with a robust benefits package before expanding funding. “Kenya has done the reverse, demanding more without offering clear value,” he says.

Income mismatch

SHA’s rigid annual contribution model also fails to accommodate irregular income cycles in the informal economy. Juma calls for flexible payment options, weekly or seasonal, similar to Rwanda’s Mutuelles de Santé, which uses decentralised, community-aligned contributions and achieves 85 per cent coverage.

Kenya’s means-testing tool, used to determine informal sector contributions, is also under scrutiny. Former Health CS Deborah Barasa told MPs some individuals were manipulating the system.

Juma recommends targeted subsidies: fully subsidising premiums for the poor and providing tiered support for low-income earners. Prof Iraki says public education on how health insurance works is vital. “Kenyans must understand the long-term value of insurance, not just its use in emergencies.”

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.