Dear Daktari,

Thank you for your informative articles. I have been doing dairy farming for a while now. One of the biggest headaches over time has been managing tick infestation in my herd.

Despite regular spraying, I have not been able to eliminate the ticks. I have even lost some of my animals to tick-borne diseases like East Coast Fever and Anaplasmosis. Apart from regular spraying, what other options can I explore to manage the problem?

Ernest Gitahi,

Kiambu

Dear Ernest, thank you for your good question and also for sharing your experience.

Ticks and tick-borne diseases are a great concern in livestock production due to the veterinary costs and impact on human health through zoonotic diseases.

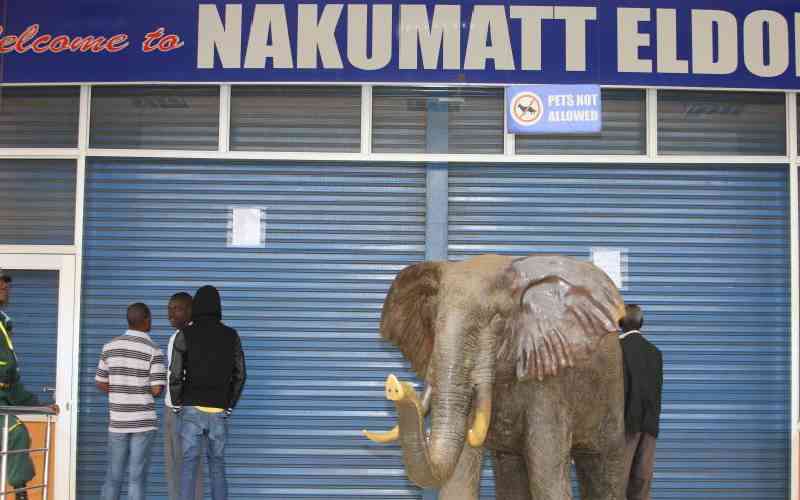

In livestock production, ticks spread diseases, cause anaemia, weight loss, reduced milk production, and death. In pets, ticks cause skin irritation and transmit diseases like ehrlichiosis in dogs.

As you rightfully pointed out, ticks are a thorn in the flesh for many farmers, and their management should be a top priority for maximum returns on their investment.

However, it is never easy, as many governments, especially in Africa, have been reluctant to eliminate ticks.

There have been attempts in countries in the West to eliminate ticks, and there are policies to that effect. This draws from the realisation that eliminating the insects calls for collective effort.

As you have rightly pointed out in your question, sometimes it is hard to control ticks on your farm when your neighbours are not doing the same.

A simple structure, like a good fence, can keep away feral dogs that can easily bring in ticks from infested farms into your farm. However, many farmers are not aware of such simple biosecurity measures. But the effective control of ticks is dependent on a number of considerations.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The first is chemical control. This method has been in use for decades despite increasing resistance to acaricides due to misuse. The misuse is through the use of incorrect concentration or wrong application, timings, or skills of application.

Acaricides are effective in reducing tick infestation and subsequently preventing tick-borne diseases when used correctly and strategically.

Methods of acaricide application include dipping, where livestock are submerged in an acaricide solution. This method maximises the reach of the acaricides on the entire body if the cattle spend enough time in the dip. However, the concentration should be monitored to ensure it remains effective.

Pour-on formulations are effective in areas with limited water sources; the acaricide is poured onto the animal's back, and it is released slowly over time. Pour-ons are relatively expensive.

Most farmers use handheld knapsack sprayers that require good application skills to target and kill ticks on the animal’s body.

The use of acaricides requires one to be cognizant of the life cycle of the ticks and, subsequently, the correct timing to ensure the entire life cycle is targeted and terminated.

Resistance to acaricides has developed over time and remains a critical challenge in acaricide use.

The continuous and indiscriminate application of acaricides has led to the widespread development of resistance in tick populations. Resistance mechanisms by ticks include genetic mutations altering target sites, metabolic detoxification by tick systems, and behavioural changes.

The second method of tick control is the use of repellents. Plant extracts from tobacco, lemongrass and eucalyptus have been used to repel ticks; they are, however, relatively ineffective as correct concentrations and volumes are never known, but they are environmentally friendly.

The third method is manual removal and grooming. Though a bit traditional, many small-scale farmers employ this method of tick control.

Manual removal using tools like tick twisters or fine-tipped tweezers minimises damage caused by tick mouthparts, thereby reducing pathogen transmission risks and also wound development.

In resource-limited settings, manual removal is often combined with dipping and acaricides to manage livestock tick infestations. Host grooming, particularly for pets and livestock, physically removes ticks before attachment, reducing the likelihood of pathogen transmission.

Livestock rotation mitigates tick infestations by managing grazing systems and reducing interactions with reservoir hosts, significantly lowering the prevalence of tick-borne diseases in livestock.

Pasture rotation delays cattle contact with tick larvae, disrupting their life cycle. As a result, larvae die from starvation or dehydration. Restricting stray dogs and wildlife access to livestock areas through fencing or barriers complements livestock rotation by limiting interactions between wildlife and livestock.

The final method is Integrated Pest Management (IPM). It refers to the integration of diverse methods, such as biological control, cultural practices, and chemical application.

IPM creates a farming system capable of adapting to changing ecological conditions and changing pest dynamics. Traditional tick control has largely relied on chemical acaricides; however, their extensive use has led to widespread resistance, environmental contamination, and residue accumulation in livestock products.

[Dr Othieno is a veterinary surgeon and the head of communications at the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) Kenya. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of FAO but his own]